Sheepshead Bay Brooklyn was segregated when I was growing up there. Jews shopped for groceries at Waldbaums, non Jews shopped at the A&P. Colorless vehicles faded by the sun and worn thin by the cold encroached upon each others spaces in the crowded parking lot. Jam packed cars off loaded one kid after another, as if they were all clown cars from the circus. Finally with the last passenger out the mom would assemble her brood and re-position everyone in the shopping wagon. That’s what we called them then.

The smallest child readied the helm in the front basket portion of the cart. Someone else usually climbed in, and still another kid hung off the rear. Anyone that couldn’t find a spot just kind of tagged along. Once stabilized, it was hope against hope that this chariot wouldn’t be thrown off-balance by an itinerant wheel, which would make the wagon wobble just enough to make it difficult to steer. The beehived stretch pant wearing mom would then make her way through the aisles, tossing in milk, bread, and several types of sugary cereal with corn flakes thrown in for the man of the house. Red meat, mayonnaise, American cheese and bananas partially covered whichever kid was in there. Eggs usually rested on the lap of the baby in the front perch. Canned vegetables, spaghetti, ketchup (used as tomato sauce) and an occasional box of cookies would begin to bury the kid riding inside. Overtaken by the mounting staples they would beckon to be taken out and walk along side.

The check out lines were always long. Some mothers let their kids buy gum or candy at the checkout stand. Mine didn’t. We waited for the cashier to manually inspect each item and ring it up. Once she had given it the once-over she would slide it to the end of the counter and a kid (usually a boy) would strategically put the groceries into a paper bag with the precision engineering of interlocking gears found inside a Swiss watch.

We didn’t know her name, nor she ours. She didn’t ask us how we were, or how we were doing in school. She did her job and the next family made its way through the line. Her smile at the end of each transaction was forced and close-lipped. Screaming kids, standing on her feet for hours at a time, she wasn’t paid to be nice. She was paid to be there.

The A&P didn’t have a parking lot. It was populated by old ladies with varying shades of either blue or pink tinged hair color who either didn’t or couldn’t drive. They walked to the store wheeling their personal vertical shopping carts lined with protective plastic, just in case it rained on the way home. Once in a blue moon my mom would send us to the A&P for something she ran out of and I would look at what filled the carts of the old women. They were buying small glass jars of coffee, biscuits wrapped in foil, Oscar Meyer bacon, containers of cream and things I didn’t recognize. Our household was Kosher. We didn’t eat bacon, and I never saw cream put into coffee until I went away to college. My dad drank it black, and my mom only drank tea. My mom filled a crystal “creamer” with milk for our guests, but the “company” that sat around our dining room table several nights a week drinking coffee and eating Entenmanns cake were never served cream. The A&P was quiet. Almost still. The difference between the two markets was as pronounced as the battle lines drawn between the Protestants and Catholics of Northern Ireland.

In the mid nineties my mom would visit my young family in Los Angeles. She integrated easily into our lifestyle and would sometimes accompany me and my girls to the market. “You would be able to buy a house in Florida for what it cost to buy a red pepper in this fancy supermarket of yours here”, she would tell me, astounded by the high prices. I was jaded and didn’t really notice, and I didn’t really care. Our business manager paid the bills. I didn’t think about money at all.

Grocery shopping in Pacific Palisades was worlds away from the supermarkets of my childhood. The average annual income in this affluent enclave of luminaries, celebrities, film executives and women who went grocery shopping with members of their household staff was more than $250,000. The battle lines in this neighborhood were not drawn by religion or political conviction, but rather were you Neiman Marcus or Barneys. Were you wearing Donald J. Pliner or Prada?

The market I shopped at looked like a museum. Not a thing was ever out-of-place. Colors coordinated, and displays never seemed to dissipate. The instant something was removed it was replaced. Nothing ever spilled, or smelled, or spoiled at Gelsons, and most assuredly, nothing ever publicly went wrong. Shoppers were ostensibly protected and greeted by name. Likes and preferences were known, and dislikes were respected. The shopping experience at this market was curated. At Waldbaums in Sheepshead Bay people waited in line to get a pound of good belly lox. At Gelsons smoked salmon was sold. I shopped there.

My husband had just announced that he would be leaving. But none the less I still needed to take care of my children. Two of my three daughters were young enough to be using diapers and that supply needed to be replaced. My very deep sense of betrayal and grief had slowed my pace but I strapped my baby into that same perch where I had seen babies safely placed so many years ago when my mother had me in tow. It took about an hour to load the cart with the essentials of our now fractured household.

“I’m so sorry Mrs. ________ your card has been declined.” Not sure that I heard her correctly I momentarily took my focus off my children and asked the neatly attired cashier to repeat herself. “The card you are trying to use is not actually in your name. You are a Mrs. You don’t actually exist. But please don’t worry Mrs. ________ we will put everything away for you.” She was paid to be nice. The store manager was summoned to soften the blow, and they both gracefully managed to smile as my children and I left empty-handed.

I drove my daughters home without the food and without the diapers. We drove back down our long driveway. I undid the seatbelt of my oldest child and took the younger two out of their car seats. Once inside I handed my girls off to the live in nanny and went into my bedroom alone. In the instant before I burst into tears I heard her ask in her lilting Spanish accent “are you okay Mrs.? As far as she was concerned that was my name.

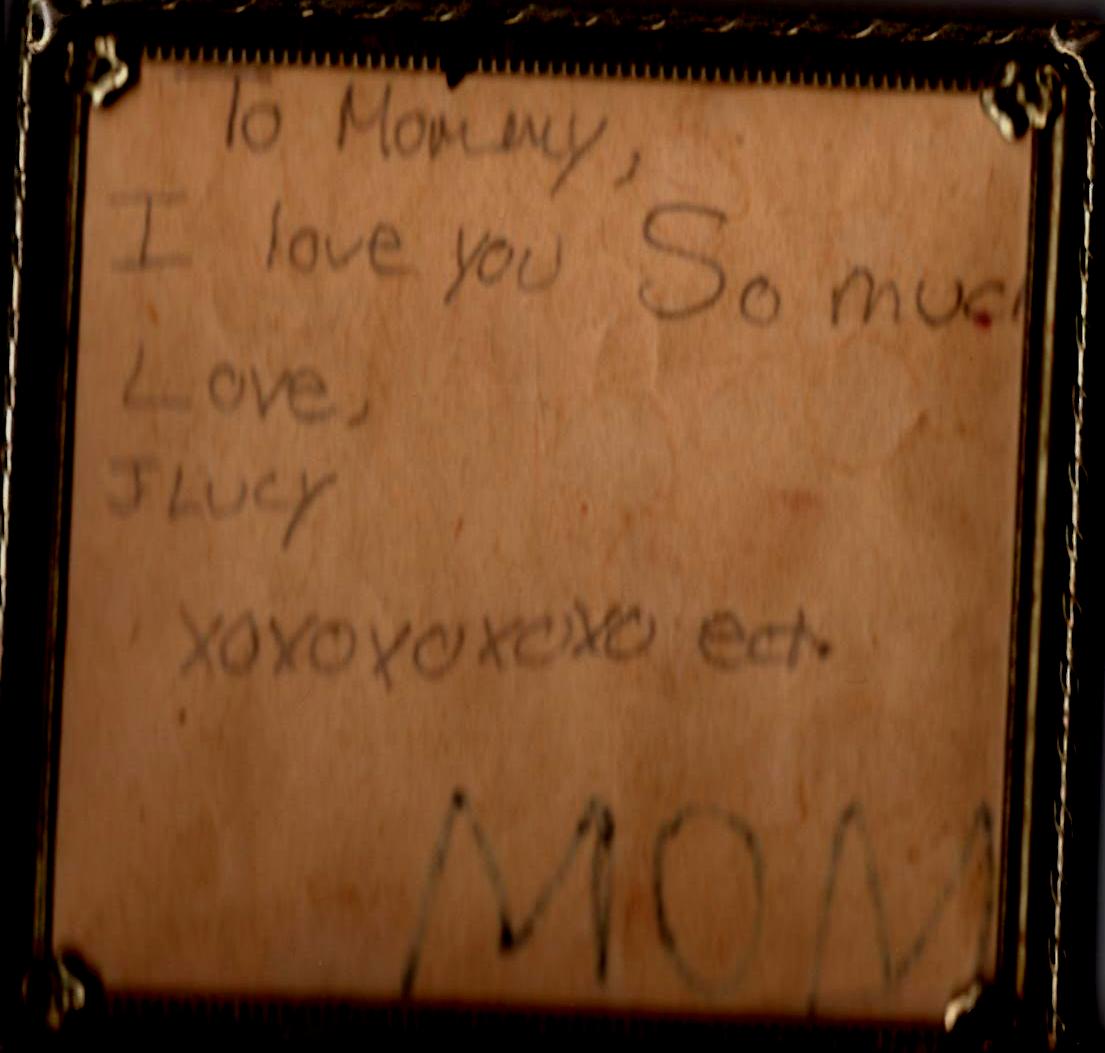

Two of my daughters are in college now and my youngest is about to start her last year of high school. So many years later and just recounting that moment stills my heart and makes me cry. Whose life did I need to prove that I had? Mine only seemed to matter if the prefix to my own name was bestowed upon me by someone else. I am not currently married, and as happy as that would make me, I will never use Mrs. before my name again.

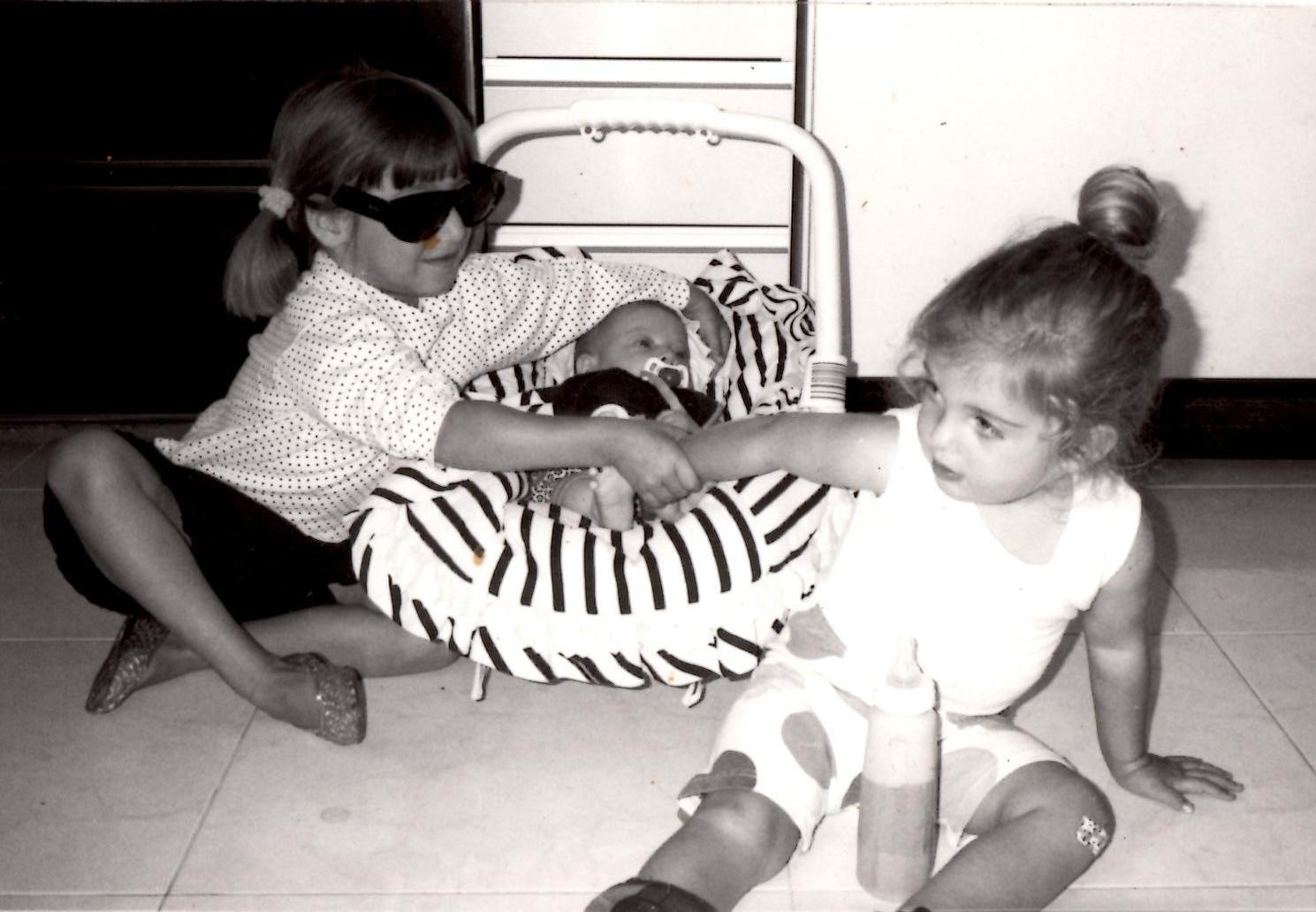

Photograph of Jill as a teenager: Julio Mitchel

Where we’ve come from, where we ended up, and where we continue to venture. It all makes quite a story doesn’t it.

Thanks for reading Raw. The details are mine, seems the story could be anyone’s.